Kesava Menon claims he’s just a journalist, sent to Islamabad on assignment 1990-1993 by The Hindu as its first Pakistan correspondent.

Don’t take that self-deprecation too seriously – he’s a cut or two above the smart reporter. A lucid writer and raconteur, he is a chronicler of his times.

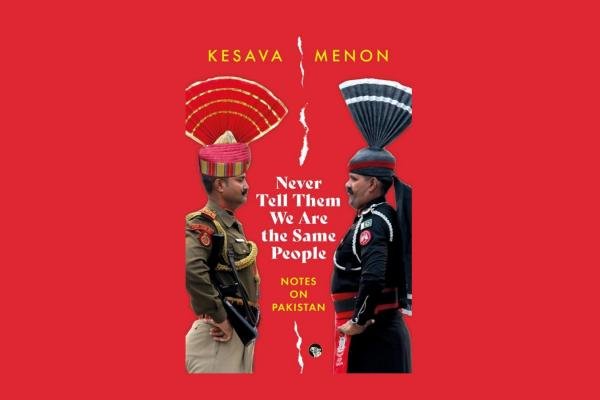

In his 2023 book, Never Tell Them We Are the Same People he shares more ethnological wisdom than you’d get from reading a bunch of boring social science PhD theses.

I do not recall having met him in Islamabad although I had been living (and still live) there some 20-plus years before his posting.

To meet wouldn’t have been easy anyway because for a Pakistani university professor like me to meet with any Indian would have had the ISI breathing down my neck.

Reading through Menon’s book, my feelings fluctuated. I endorse his position that the Pakistani military – which has controlled the country either upfront or from the shadows – has engineered an anti-India mindset amongst my countryfolk and helped to create a “collective neurosis.” Indeed, how else could this institution have served itself the delicious privileges it enjoys?

But we must not be unfair: elites everywhere, political and military, play the time worn game of stirring animosities against another country for immediate gains.

These days you need only look to see how Putin & co have succeeded in demonising Ukrainians. Or, for that matter, the unflattering images the India’s political elite have created about neighbouring countries, not just Pakistan.

Menon’s is a work replete with examples of his personal encounters that could be leveraged both ways. They are informative and perceptive, but his conclusions can sometimes be dubious.

In the very first chapter the author stridently claims that Indians don’t really fear Pakistan (and presumably its nukes as well).

Instead, a “far, far greater proportion of us [Indians] look at Pakistan with loathing and contempt, an imbalance that exposes the futility of a policy of terror.” Ergo, we are not the same people.

So, notwithstanding occasional bonhomie, and how Pakistanis and Indians naturally gravitate towards other when they are in the West, he hints that deep down we are different and so can never truly be friends. Ah, but doesn’t that smack of the ‘Two Nation Theory’?

Before we rush to such a stark conclusion, perhaps we need to consider other people’s experiences as well. An example from earlier this month:

a maverick Pakistani motor-cyclist Abrar Hassan took a 30-day 7000 km trip around India on his BMW adventure bike. His uploaded YouTube videos show welcoming locals riding along with their motorbikes soon after he crosses the Wagah border.

Given the near-impossibility of a Pakistani getting an Indian visa (we’re all supposed to be terrorists, remember?) this shows that the move to demonise hasn’t worked all that well.

To me, my own experience is far more persuasive. The love and affection I received in 2005 during my four-week-long lecture tour of seven Indian cities – Delhi, Mumbai, Poona, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Bhubaneswar – were enormously positive experiences.

That was a time when to get an Indian visa wasn’t too difficult. Every day of my visit was filled with lively interactions with school students, college and university teachers, and physics colleagues at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, as well as two Indian Institutes of Technology.

One 12-year-old in a run-down Delhi school had never seen a Hindi-speaking Pakistani (I was actually speaking Urdu).

She came to the front of the class and poked me with her finger to see if I was real, and then hugged me.

The author expertly relates several amusing anecdotes from his days in Pakistan some thirty years ago.

I can share my more recent ones from India. On the way to visiting my friend Rajmohan Gandhi in Gandhinagar, my wife and I passed through Ahmedabad.

Thanks to a new law, only foreigners could purchase alcohol. Pakistanis, of course, are the most foreign of foreigners! Sadia and I were only too happy to oblige all who asked.

We got quite a kick out of the fact that back home possession of alcohol could put us in jail but a green passport in Gujarat had made us wildly popular in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state.

Such silly stories tell us a little – but only a little – about another country. There are, of course, far larger issues that stem from an incredibly bloody genesis.

There is no denying that, since the late 1980s, the Pakistani military establishment secretly set up jihadist insurgents to wrest Kashmir away from India. I am direct witness to what the author describes as “wild-eyed mullahs exhorting even wilder-eyed and frothier-mouthed hordes to undertake jihad.”

This miserably stupid policy eventually boomeranged and put the army itself in their cross hairs, the final straw being the slaughter of over 120 children at the Army Public School in Peshawar in December 2014.

Fortunately, that episode of jihad is now behind us. Thanks to the pressure generated through the the Financial Action Task Force, the global watchdog, militant leaders like Hafiz Saeed and his lot have been banished from the scene.

The author decries the “hysterical animosity” of the Pakistani media while correctly noting that the Punjabi establishment – both the military and the landholding class – had imposed their world view on the country as a whole.

However, he should have added that Balochistan, Sind, and Gilgit-Baltistan never quite went along with Punjab and the establishment media. Also, although only a few of us spoke out, let it be noted that quite a few Pakistanis had opposed the use of terror as a weapon even during the heydays of jihad.

As I have just argued, all communities are imagined. So, are we Pakistanis and Indians the same people? Well, yes and no. Both answers are important to understand.

First: yes, we are the same! It’s a no-brainer that a lot of Indians and Pakistanis look alike, enjoy the same genres of music and drama, are cricket crazy, and have the same mental makeup. Everyone loves Lata Mangeshkar.

Despite China and Pakistan being strategic allies, and notwithstanding various inducements to intermingle (such as the massive Pak-China Centre in Islamabad), one does not see significant Chinese-Pakistani bonding.

Pakistani students studying in China, or Chinese workers in Pakistan, find it difficult to overcome the ethnic and linguistic divide.